C++QED is a framework for simulating open quantum dynamics in general. It addresses the following problem: somebody who writes simulation code for a single quantum particle, mode, or spin today; tomorrow will want to simulate two or ten such systems interacting with each other. They want to reuse the code written for the single-system case, but this turns out to be rather difficult for naively written code, due to the algebraic structure of quantum mechanics. C++QED facilitates this task, providing a framework for representing elementary physical systems (“elements” – particle motional degrees of freedom, harmonic oscillator modes, spins, etc.) in such a way that they can immediately be used as constituents of composite systems as well. Dynamical simulations of such systems can be performed with a set of tools provided by the framework.

Historically, C++QED originated from the simulation of systems in cavity quantum electrodynamics (CQED – hence the framework’s name). Its approach subsequently proved particularly useful in the wider context of quantum optics [19] [20] [13], as this field typically addresses systems composed of several diverse “small” subsystems interacting with each other; but also in atomic physics or quantum many-body physics [19] [10] [12].

The framework is capable of simulating fully quantum dynamics (Schrödinger equation) of any system, provided that its Hamiltonian is expressed in a finite discrete basis, and open (Liouvillean) dynamics, if the Lindblad- or quantum-jump operators are expressed in the same basis. Apart from this, the only limitation on the simulated system is its dimensionality: with present-day hardware, a typical limit is

Since at present C++QED does not offer any special tools for addressing many-body problems, only “brute-force” calculations, this limitation means that such problems cannot be pursued very far.

C++QED saw a first, prototype version developed between 2006–2008, a purely object-oriented design, which was partially documented in [18]. The second version, defined by the multi-array concept and compile-time algorithms, has been developed since 2008. By today it is quite mature, robust, and trustworthy, having passed thousands of tests also in real-life situations. It is an open-source project, hosted by SourceForge.net, and it builds only on open-source libraries, such as

The framework provides building blocks (refered to as “elements”) for composite quantum systems, which come in two types:

The representation of composites was designed in such a way that recursivity is possible in their definition: a composite system can act as a building block for an even more composite system. (As yet, no working example of this possibility has been implemented; but e.g. we may think about systems composed of several atoms with both external and internal degrees of freedom.)

Time-evolution drivers are provided for systems such composed. At the moment three kinds of time evolution are implemented:

These modules together provide a high-level C++ application-programming interface. Normally, they are assembled in high-level C++ programs (which we will refer to as “scripts” throughout), which specify the system and what to do with it. Example scripts are given in the User Guide – the level-1 interface of C++QED. Hence in normal usage, to each physical system there corresponds a program which uses the framework as a library.

The framework strives to facilitate the implementation of new building blocks. New free systems and interactions are best implemented by inheritance from a class hierarchy (the classes making up the structure namespace in the framework) which provides a lot of services. There are classes representing quantum operators with their appropriate algebra (the quantumoperator namespace).

A very important principle during the design and implementation of the framework was to process all information which is available at compile time, at compile time. This leads to optimal separation between the two types of information, the information available at compile time and the information becoming available only at runtime, and allows for maximal exploitation of compile time. Normally, a script compiled once will be used many times for data collection.

We strive to recycle code as much as possible, the two most powerful ideas supporting this are

In compiled computer languages, source code goes through two stages to produce computational data:

(In contrast, in interpreted languages these two stages are fused.) Usually, calculations are performed during stage 2 only. C++ template metaprogramming (TMP) provides a Turing-complete language [1] for stage 1, whose basic operands are the C++ types. Hence, stage 1 is useful not only for performing certain optimizations, but through TMP it becomes possible to shift calculations from stage 2 to here. This possibility was demonstrated in Appendix A in [21].

Let us see how TMP comes about in the definition of composite quantum systems. Such systems have several quantum numbers, and their state vector is most conveniently represented by an entity having as many indices (this is referred to as the rank or arity of the system or state vector: unary, binary, ternary, quaternary, etc.). Very many constructs in the framework have RANK as a template parameter.

Consider the following two possibilities:

If we have two state vectors of different arity  and

and  , then in the first case they have to be represented by entities of the same type, while in the second case they can be different types. Therefore, a nonsensical expression like

, then in the first case they have to be represented by entities of the same type, while in the second case they can be different types. Therefore, a nonsensical expression like

![\[\Psi^{(\text{rank1})}+\Psi^{(\text{rank2})}\]](form_2.png)

causes a probably fatal error in the first case, which can be detected only at runtime, possibly after a lot of calculations. In the second case, however, such an expression can be a grammar error prohibiting compilation. Furthermore, for indexing such a state vector, in the first case a runtime loop is needed, which is not necessary in the second case, where this loop can be unraveled at compile time.

In C++QEDv2, since a script corresponds to a given physical system, the layout of the system is known at the time we compile the script , so that its arity is naturally also known. This then implies a lot of further compile-time calculations. Furthermore, many errors related to inconsistencies in the system layout can also be detected at compile time.

Very roughly, we can think about C++QEDv2 scripts as C++ programs which exploit the template mechanism of C++, to generate (lower-level) C++ programs in such a way that in the resulting executable all compile-time information is encoded to yield a maximally effective and safe application for the given physical system.

In C++QEDv2, compile-time resource requirement scales with the complexity of the simulated system, while runtime resource requirement scales with the total dimensionality. Hence, compile time can be best exploited when the system is composed of a lot of subsystems, all with low dimensionality. As an example, we might think about several spin one-halves with complicated interactions.

In terms of simulation software available for open quantum systems, a very remarkable project is QuTip [8] [9] , which appears to be a Python reimplementation of the originally Matlab-based Quantum Optics Toolbox [16]. There, the interface is built on quantum operators, and general usage involves a considerable amount of boilerplate.

Since C++QED operates with elementary physical systems, the interface is of a much higher level than in the QuTip.

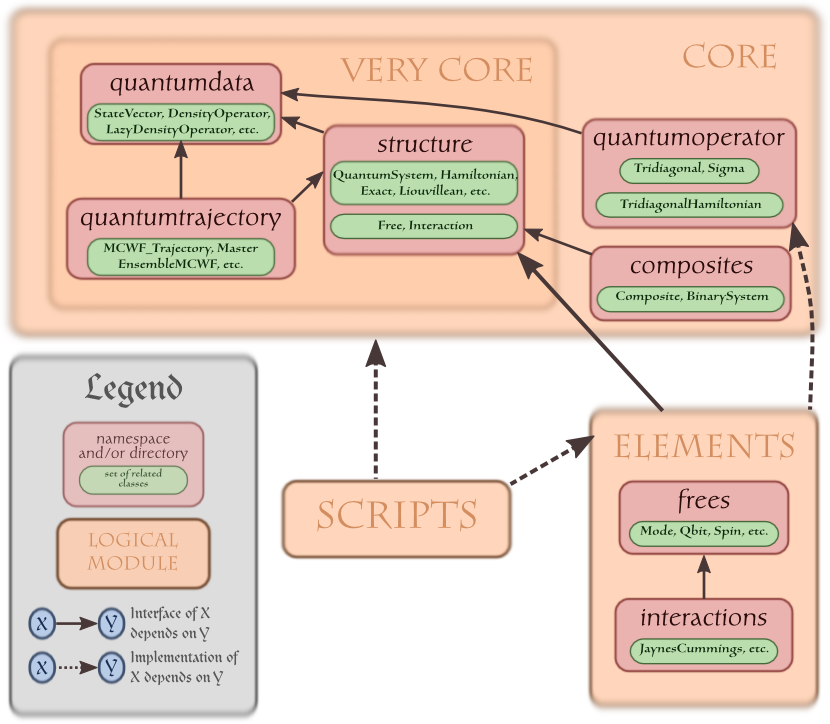

This structure is reflected on the build system, dependencies being very strictly defined and observed throughout.

The “very core” is composed of the following namespaces:

Within “core”, a separate tract is constituted by the quantumoperator namespace, which defines classes for representing special operator structures to facilitate the implementation of new elements. At present, tridiagonal and sparse matrices are implemented: this covers most of the problems we have come across in quantum optics so far.

Composites belong to “core” as they represent the most fundamental design concept of the framework. They are at the moment BinarySystem and Composite.

Elements come in two brands: in this tract, free elements are independent, while interaction elements depend on frees. Most free and interaction elements are implemented with the help of special operator structures, so that their implementation depends on the quantumoperator namespace. Both brands of elements derive from at least one of the classes in namespace structure.

Scripts use both the core and the elements of the framework for their implementation. Separate shared libraries are created out of the foregoing tracts, which may also link against the third-party libraries like GSL, FLENS, etc. Scripts in turn link against these C++QED libraries, so that the whole framework is stored in memory in a fully shared way.