In the following we will cover how to use the framework on the highest level. The highest level is a C++ program, which is called a script . Such scripts can be written either in C++ or in Python, using the Python frontend of the framework.

A script creates an executable which defines and simulates a system of a particular layout. All information pertaining to the layout of the system is processed at compile time. Our compile-time algorithms can be regarded as C++ programs generating C++ programs in such a way that in the resulting executable all the compile-time information is encoded to yield a maximally efficient executable for the given layout.

A script is composed of a part where the system is specified, and another, where we do something with the system, most notably simulate its time evolution in one of the ways described in the Basic specification .

In this section, the examples are taken from the field of (moving-particle) cavity QED.

In order to experiment on your own, you need a CMake project which holds the scripts you write. The easiest approach is to copy the directory CustomScriptsExample to some other location and start with that. In the project directory, create a build directory build and configure the project:

mkdir build cd build cmake -DCMAKE_BUILD_TYPE=Debug ..

For the build type, choose the one that fits the configuration of the framework. If you installed C++QED from Ubuntu packages, you can use both Debug and Release here.

Every time you add a new script source file, you have to run cmake again so that it will be picked up by the build system. To build all scripts, call

make

or to build only a specific script, call

make <scriptname>

You can also open your new scripts project in an Integrated Development Environment (IDE), see here for details.

The simplest case is that of a free system alone. Assume that this free system is a lossy resonator mode, which may be driven (“pumped” with a laser) as well. Its evolution can be described by the following Master equation:

![\[\dot\rho=\frac1{i\hbar}\lp\HnH\,\rho-\rho\HnH^\dag\rp+\kappa\,a\rho a^\dag,\quad\HnH=-\hbar(\delta+i\kappa)\adagger a+i\hbar\lp\eta\adagger-\hermConj\rp.\]](form_3.png)

We begin with defining the system, which is trivial in this case because the required free element is already given:

PumpedLossyMode mode(delta,kappa,eta,cutoff);

where cutoff is the cutoff of the mode’s Fock space.

The system defined, we can already use it for several things, e.g. to calculate the action of the system Hamiltonian on a given state vector, or export the matrix of the Hamiltonian for exact diagonalization. Suppose we want to do something more: run a single MCWF trajectory. The system is started from a pure initial state, specified as

quantumdata::StateVector<1> psi(mode::coherent(alpha,cutoff));

that is, the mode is in a coherent state with amplitude alpha. StateVector<1> means that it is a state vector of a system featuring a single quantum number (unary state vector).

Next, we define our Monte Carlo wave-function trajectory driver:

quantumtrajectory::MCWF_Trajectory<1> trajectory(psi,mode,...a lot more parameters...);

The first two parameters are clear, the only thing to note is that psi is taken as a reference here, so the initial psi will be actually evolved as we evolve the trajectory. A lot more parameters are needed, pertaining to the ordinary differential equation stepper, the random number generation, etc., for which default values are also provided (see below).

The trajectory can be run with

run(trajectory,time,dt);

This will evolve trajectory for time time, and display information about the state of the system after every time interval dt. The set of information (usually a set of quantum averages) displayed is defined by the system. There is another version, which can be invoked as

run(trajectory,time,dc);

Here, dc is an integer standing for the number of (adaptive) timesteps between two displays.

In the above, the necessary parameters must be previously defined somewhere. Parameters can come from several sources, but the most useful alternative is to have sensible defaults for all parameters, and to be able to override each of them separately in the command line when actually executing the script with a given set of parameters. This allows for a fine-grained control over what we want to accept as default and what we want to override, and the command line never gets crowded by those parameters for which the default is fine.

This possibility is indeed supported by the framework. Consider the following program:

The corresponding script in Python

This is a full-fledged script, so if you copy this into directory CustomScriptsExample as temp.cc, it will compile. Don't forget to re-run cmake in order to pick up the new script and call make temp in the build directory. (In fact, the script is already there in CPPQEDscripts as tutorialMode.cc.)

Let us analyse the script line by line:

parameters::ParameterTable is a utility module storing all the parameters of the problem, and enabling them to be manipulated from the command line. It can store and handle any type for which i/o streaming operations are defined.

We instantiate the actual parameters for the time-evolution driver(s) and the mode, respectively. All the modules in the framework provide correspondingPars... classes. Pars... class is defined, but since at those points there is no knowledge about the details of the problem, these cannot always qualify as “sensible”.The command line is parsed by the parameters::update() function.

We instantiate our mode, but now instead of the concrete PumpedLossyMode class, we are using a maker (dispatcher) function, which selects the best mode class corresponding to the parameters. The possibilities are numerous: a mode can be pumped or unpumped, lossy or conservative, finite or zero temperature, and it can be considered in several quantum mechanical pictures. Each of these possibilities is represented by a class, and these classes all have a common base ModeBase.

The mode::Ptr is a smart pointer to this type, so that it can “store” either of these classes. For example, if  and

and  , then we will have a Mode; if

, then we will have a Mode; if  is nonzero, a PumpedMode; and if both are nonzero, a PumpedLossyMode.

is nonzero, a PumpedMode; and if both are nonzero, a PumpedLossyMode.

Sch, UIP and no suffix mean Schrödinger picture, unitary interaction picture, and “full” interaction picture, respectively. If the system is not lossy, then the latter two coincide. Schrödinger picture is provided mostly for testing purposes, the performance is usually not optimal in this case.

What we are telling the maker function in the same line is that the picture should be unitary interaction picture. Alternatively, we could add this as a parameter as well, which can be achieved by replacing update with

QM_Picture& qmp=updateWithPicture(p,argc,argv);

mode::StateVector is just another name for a unary quantumdata::StateVector, and mode::init is just another dispatcher, this time for the initial condition of the mode.

The function evolve is a dispatcher for different evolution methods and the different versions of trajectory::Trajectory::run. So with this, the evolution mode can be changed from the command line, e.g. depending on the dimension of the problem – while for low dimension we may use Master equation, for larger dimension we may need to switch to an ensemble of quantum trajectories. The possibilities are:

--evol master Full Master equation--evol single Single Monte Carlo wave-function trajectory--evol ensemble Ensemble of Monte Carlo wave-function trajectoriesIf we specify the --help option in the command line, the program will display all the available parameters together with their types (the less readable the more complex the type is), a short description, and the default value.

An example command line then looks like:

PumpedLossyModeScript --eps 1e-12 --dc 100 --deltaC -10 --cutoff 20 --eta "(2,-1)" ...

--dc is nonzero, then always the dc-mode trajectory::Adaptive::run function will be selected by the evolve function above, regardless of the value of --Dt. The latter will only be considered if --dc is zero because in this case the deltaT-mode trajectory::Trajectory::run function will be selected. There is a similar relationship between --minitFock and --minit: the former will always override the latter.Imagine we would like to define a more complex system, where a two-level atom (qbit) interacts with a single cavity mode with a Jaynes-Cummings type interaction. Both the qbit and the mode may be pumped, and they may also be lossy. The full non-Hermitian Hamiltonian of the system in the frame rotating with the pump frequency reads:

![\[\HnH=-\hbar\lp\delta_\text{Q}+i\gamma\rp\,\sigma^\dagger\sigma+i\lp\eta_\text{Q}\,\sigma^\dagger-\hermConj\rp-\hbar\lp\delta_\text{M}+i\kappa\rp a^\dagger a+i\hbar\lp\eta_\text{M}\, a^\dagger-\hermConj\rp+i\hbar\lp g^*\sigma a^\dagger-\hermConj\rp\]](form_7.png)

First, we need to define the free elements of the system:

PumpedLossyQbit qbit(deltaA,gamma,etaA); PumpedLossyMode mode(deltaC,kappa,etaC,cutoff);

Next, we define the interaction between them:

JaynesCummings act(qbit,mode,g);

Now we have to bind together the two free subsystems with the interaction, which is simply accomplished by:

binary::Ptr system(binary::make(act));

In the case of a BinarySystem the complete layout of the system can be trivially figured out from the single interaction element. Similarly to mode::Ptr, binary::Ptr is an entity which can store all the versions of BinarySystem (for example, conservative or lossy).

Our next task is to define the initial condition:

StateVector<2> psi(qbit::state0()*mode::coherent(alpha,cutoff));

This is to say that the qbit is in its  state, and the mode is in a coherent state

state, and the mode is in a coherent state  . Both states are of type quantumdata::StateVector

. Both states are of type quantumdata::StateVector <1>, meaning that they are state vectors featuring a single quantum number, and * means direct product of state vectors, so the result here is a quantumdata::StateVector <2>. Direct product is not commutative, and we have to comply with the order defined above for the free systems, which is Qbit followed by Mode.

Alternatively, we could have said

StateVector<2> psi(init(pq)*init(pm));

From this point on, usage is the same as we have seen above for the mode example. Since in this case the system is a BinarySystem, it will reach into its constituents for what system characteristics to display, supplying either with the corresponding reduced density operator (cf. Slicing a LazyDensityOperator), which contains all information on the state of the subsystem.

If the system is not to be used for anything else, just for being evolved, we can avoid having to invent all these redundant names like qbit, mode, act, system, trajectory, and create everything in place. In this case a full-fledged script can be as terse as (cf. CPPQEDscripts/tutorialBinary.cc):

The corresponding script in Python

Here qbit::make will dispatch exactly the same possibilities that we have seen for the mode above.

If there are more than two free subsystems, the system can be much more complex. The number of possible interactions rises combinatorically with the number of frees. This is the situation when the full potential of C++QED is displayed.

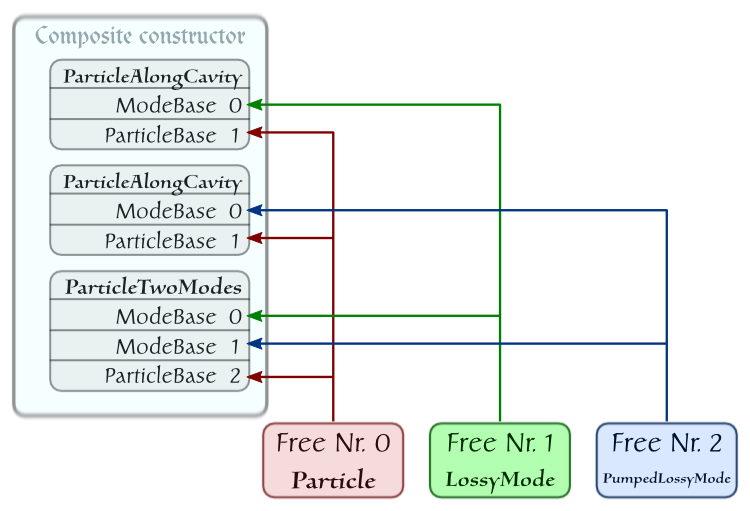

Assume we want to define a system where a particle is moving along the axis of a ring cavity, and is interacting with two counterpropagating running-wave modes of the cavity. Both of the modes are lossy, and one of them is pumped; the particle is not pumped [13]. This system consists of three subsystems, a particle, and the two modes. There are three interactions:

We can lay out the system as the following simple network:

The Composite module of the framework is designed to represent such a network. Assume the following definitions are in effect:

// Instantiate Frees Particle part (...); LossyMode plus (...); PumpedLossyMode minus(...); // Instantiate Interactions ParticleAlongCavity actP(plus ,part,...,MFT_PLUS ); ParticleAlongCavity actM(minus,part,...,MFT_MINUS); ParticleTwoModes act3(plus,minus,part,...);

Here MFT_ means the type of the mode function and can be PLUS, MINUS, COS, and SIN [18].

Then the system can be created by invoking the maker function for Composite with the special syntax:

composite::make(_<1,0> (actP),

_<2,0> (actM),

_<1,2,0>(act3));

What we are expressing here e.g. with the specification _<1,2,0>(act3) is that the 0th “leg” of the interaction element ParticleTwoModes, which is the mode plus, is the 1st in our row of frees in the network above.

The 1st leg, the mode minus is the 2nd in the row; and the 2nd leg, the particle is the 0th in the row of frees. The legs of interaction elements cannot be interchanged, and we also have to be consistent with our preconceived order of frees throughout. The three _ objects above contain all the information needed by the framework to figure out the full layout of the system.

Any inconsistency in the layout will result in a compile-time or runtime error (cf. the description @ Composite). The user is encouraged to play around creating layout errors deliberately, and see what effect they have.

The actual C++ type of a Composite object returned by such an invocation of composite::make is quite complex, but a maker metafunction facilitates referencing it

composite::result_of::Make<_<1,0>,_<2,0>,_<1,2,0> >::type // type of the above Composite

auto keyword to let the compiler figure out the type returned by composite::make, if we need to store the object in a variable.A full-fledged script in the terse way may read as:

The corresponding script in Python

A notable additional feature as compared to previous examples is that since now we have two modes in the system, we somehow have to differentiate between their parameters in the command line. This is achieved by the "P" and "M" modifiers added to the constructors of Pars... objects, so that e.g. instead of --cutoff we now have the separate options --cutoffP and --cutoffM.

Although now all the frees have the general types contained by the mode::Ptr classes, their possible types are still restricted by the Pars... classes, such that e.g. plus can never become pumped.

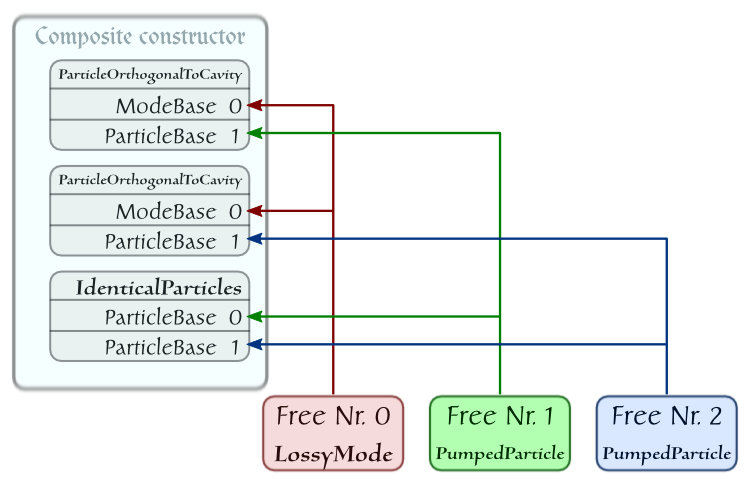

Finally, we are reviewing one more example, which displays another feature reflecting a basic principle of quantum physics: if two systems are identical, they are indistinguishable. In the language of C++QED this means that a single object is enough to represent them.

Consider two identical pumped particles moving in a direction orthogonal to the axis of a cavity sustaining a single lossy mode [19] . The layout of the system is:

The corresponding script reads:

The element IdenticalParticles has no dynamical role, it can be used to calculate and display characteristics of the quantum state of the two-particle subsystem.

Each trajectory output has a header part. First, the full command line is echoed, then C++QED and other linked library versions are displayed.

This is followed by a summary of the parameters of the given simulation. The header displays system characteristics, and lists the decay channels of the system, each decay channel endowed with an ordinal number. This list facilitates the interpretation of log output.

Following the header part, the time-dependent simulated data is displayed, organized into columns. The first two columns are time and timestep, then separated by tab characters, the data stemming from the different subsystems follows. A key to the data with a short description of each column is provided at the end of the header part.

The output of real numbers has a precision of three digits by default, this can be overridden by the --precision option. This characteristic propagates throughout the framework starting from trajectory headers:

Log output during or at the end of the trajectory is governed by the --logLevel option. When nonzero, the trajectory drivers will record certain data during the run.

For a single MCWF trajectory, there are several logging levels:

logLevel<=1 No log output during the trajectory.logLevel>0 At the trajectory’s end, a summary and a list of the jump time instants and jump kinds (ordinal number of the jump which occured) – this list is usually considered the actual quantum trajectory.logLevel>1 Reporting jumps also during the trajectory evolution.logLevel>2 Reporting dpLimit overshoots and the resulting stepsize decrease also during trajectory evolution.logLevel>3 Reporting the number of failed ODE steps in the given step of the trajectory evolution.For an ensemble of MCWF trajectories, if logLevel>0, we get accumulated values of the logged characteristics of the element MCWF trajectories.

This is followed by a time histogram of the occured quantum jumps in all decay channels. The preparation of the histogram is governed by two parameters: --nBin, the number of bins, and --nJumpsPerBin. If the former is zero, then on the basis of latter a heuristic determination of the number of bins occurs in such a way that the average number of jumps equal --nJumpsPerBin. If the total number of jumps is smaller than 2*nJumpsPerBin, no histogram is created.

For a single MCWF trajectory, time averaging of the displayed system characteristics can be turned on with the --timeAverage switch. The time averages will be displayed at the end of the trajectory organized into columns in the same way as the displayed system characteristics are during the run.

A relaxation time which is left out from averaging at the beginning of the trajectory can be specified with the --relaxationTime option.

Trajectory output goes to the standard output by default.

Alternatively, an output file can be specified with the --o option. In this case, log output during the trajectory will still go to the standard output, which can be piped into another file.

The feature described in this subsection relies on Boost.Serialization installed on the system. If this library is not available, these features get silently disabled.

For all the trajectory types (quantumtrajectory::Master, quantumtrajectory::MCWF_Trajectory, quantumtrajectory::EnsembleMCWF) it is possible to save the complete state of the trajectory. E.g., for a single MCWF trajectory, this involves the random-number generator internal state, the ODE-stepper internal state, and the full state vector of the system (plus log state and eventually also the time-averaging data).

If the trajectory is started with a specified output file as --o <filename>, then at the end of the trajectory the final state will be saved into a file named <filename>.state. This allows for eventually resuming the trajectory to continue for a longer time, which results in exactly the same run as if the trajectory has not been halted.

Any state file can also be used as initial condition for a new run through the --initFileName option.

It is also possible to damp out trajectory states during the run. The frequency of state output is defined by the --sdf option. This allows for postanalysing the state of the system with machine precision.

All trajectories can be configured to automatically stop upon reaching steady state. This is most useful for trajectories that do normally relax to a steady state like Master equation and ensemble of MCWF trajectories. Automatic stopping happens on the basis of the displayed characteristics of trajectories, and can be configured by two parameters, --autoStopEpsilon <double> and --autoStopRepetition <int>. Automatic stopping occurs when the line just displayed has a relative deviation less than autoStopEpsilon from the average calculated from the last displayed lines numbering autoStopRepetition. (The first column which is time is omitted.)

Putting autoStopRepetition to zero means turning off this feature.

The feature described in this subsection relies on the FLENS library, without which it gets silently disabled.

In a composite system we may want to assess the entanglement between two parts of the system. This can be done using the negativity of the density operator’s partial transpose [17]. Since this quantity depends on the density operator in a non-linear way, this makes sense only in the case of Master-equation evolution or an ensemble of quantum trajectories.

If we want to assess the entanglement for a single trajectory, this can be achieved by choosing ensemble evolution and setting the number of trajectories to 1.

Since the negativity of the partial transpose can be used for a bipartite system only, we have to partition our composite system into two. The subsystem to be considered as one part of the two has to be specified in an additional compile-time integer list to the evolve() function.

Assume e.g. that in the above example we are looking for the entanglement between the two particles together as one part, and the mode as the other part. Then the invocation of evolve is modified as

evolve<1,2>(psi,system,pe);

We simply have to list in the compile-time argument list the ordinals of those frees that consist one part. Of course, in this case this is equivalent to

evolve<0>(psi,system,pe);

The negativity will appear as the last column in the system characteristics display during the run, separated by a tab character from the other columns.